This article is about a project that I recently finished and delivered. The point of this article isn't to talk about the technical nitty-gritty of how it works, or why it works, or how many cans of Monster it took me to complete it (hint: I drank a lot of Amp, too). This article is about me spending the vast majority of my career as a backend engineer, the fear of branching into frontend engineering, why I needed to do it, and why I needed to finish this project. This is about some of the mental hurdles that I faced and how I overcame them. This is about the need to finish something and to stop growing the list of "shit I started and forgot about" pile.

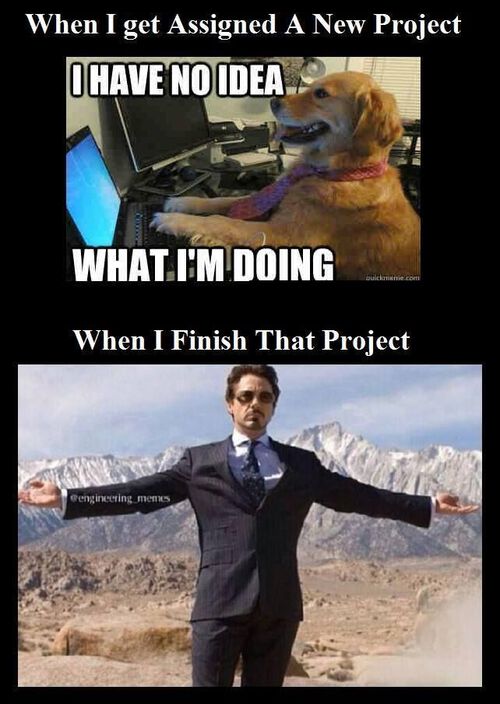

Really, what I'm chasing is this:

- Totally stolen from Google image search

How This Journey Started

I skydive in a discipline called CRW (canopy relative work). It's basically the art of flying parachutes into each other and not getting tangled or wrapped or dead, and then doing it again even if you did. It's definitely a waste of Jet-A and money, but it's still cheaper than owning an airplane, so it's one of the ways that I choose to fly. Anyway, a big part of this discipline is video debriefing. The person who is the most scared or values their life the most says, "wow, that's dumb...can I fly behind you with a camera?" and then some other weirdo on the ground says, "Hey, can we watch that video and talk about how we did?" There's a technical challenge here: How do we get the video from the person that has self-respect and self-preservation to the person who is trying to give you critique on how to not kill yourself? Bonus points if you can also get the videos to all the participants on that jump. This challenge arises from the fact that at a large event, there are several groups flying or debriefing at a time, and handing around SD cards only gets you so far. People sometimes lose the cards, or the cards get mixed up, and then chaos ensues.

This seems like something I can do! As a backend engineer, I see a few natural entities/models: the event, the video, the jump, participants, maybe a tagging system, and maybe a rating system to show how many jalapeños worth of spicy happened on that jump. Easy-peasy; that's totally a job that the Django REST Framework can make easy work of; there's even a cookie cutter project to cut down on a lot of the setup overhead. Anybody and their mom should be able to do this!

Reflections on Being a Backend Engineer: Everyone Uses Your Shit and Doesn't Know it

Great, I sink a few nights/hours into a backend API and have something reasonable. Cool. Sweet. Word. Gnar.

Now what?

I could just ask users to form cURL requests, but it turns out that people would rather stick their toes into a blender than do that. It turns out that most folks don't actually speak HTTP. SYN and ACK aren't TCP messages to these people, but rather a weird way of saying, "snack." This is a problem that I've hit over and over and over again: My work (my backends) power sooo many things, but are essentially useless on their own. In this case, this backend is not intended for some horde of engineers to write other services against (though they could). Rather, my intent is for end-users to be able to use this stuff. I need a frontend.

I'm not a frontend engineer.

I feel like I've hit this roadblock so many times and have failed to overcome it. I've written interesting backends that do cool things, like water plants, or control LEDs, but I've always failed to put a frontend on it. Those projects have remained toys or hobbies because they're essentially useless to anyone else. I can't even release them as open-source and expect any sort of adoption from anyone other than fellow engineers; they're useless to most people. They're almost as useless as CRW. Or skydiving. Or most people. Useless.

Why Aren't You a Fullstack Engineer?

Aside from thinking the term is just silly, I learned Javascript back before the ES6 days. This was well before things like the React and Node frameworks existed. At this point in the Jurassic era, things like jQuery ruled the land. There were tons of cross-browser Javascript quarks. So many so that entire websites were dedicated to tracking them and libraries like jQuery were trying to insulate developers from having to deal with them. The web browser just seemed like an incredibly insane place to me; how could anyone possibly develop anything good there? How could anything but absolute madness ensue? Screw that. I chose to steer myself to a place where I felt like I could control my runtimes. By choosing backend development, I could choose to control my OS, language runtime version, and library versions. I could build something completely repeatable. In short: the web browser and all of its insanity years ago scared me.

Self Improvement Time: I Have to Learn Some Frontend Skills, and That Comes With Hurdles

Uuuuugh. I hated this realization. In times past, I taught a night course on an intro to HTML, CSS, and Javascript. One would think that I had enough tools to dive into ES6 and React and all the other shiny things that came out of the evolution of the JS ecosystem. You'd be right, but I certainly didn't feel that way. Since my first foray into the web browser, things had become significantly more complex. The frameworks were more complex; the browser itself was more complex, allowing for more capabilities; the packaging system was more complex; there were build systems you had to learn. This seemed really, really daunting to me. Do I really have to do this? Was this really necessary?

Yes, It Was

I have a career coach that I talk to once every two weeks. Sometimes we talk about specific workplace nonsense and how to navigate it. Some of it has been on other self-development and career satisfaction. During one of these sessions, we discussed my want to someday create a startup and some of what I worry about in such a venture. One of my biggest fears is simply not being able to deliver. The fear of never getting an MVP out. The fear of not having something to iterate on. The fear of what I do when I hit this slump:

The image above is almost every engineer. When it's work related, we push through because we're hungry and need money and haven't learned to create infinite wealth from ChatGPT yet. When it's a side project, some of us (definitely I) tend to give into that resistance and ultimately give up. Countless memes and sentiments have been shared on Reddit about how software engineers start and abandon side projects like Valve abandoned Team Fortress 2. For whatever reason, we collectively seem to struggle with this. I definitely struggle with this.

This isn't just about my realization that I needed to learn some frontend skills in order to solo-prototype something. This is about how I handle the mental hurdles that come along with the territory.

What Mental Hurdles Did I Encounter?

If I'm going to feel like I have the ability to finish something, I need to do it: I need to actually finish something. Even if it never got used or adopted or saw the light of day, I need to get an MVP into a usable state simply to demonstrate to myself and others that I could. There are tons of free and open source tools out there. Tons of guides, articles, and documentation. The only thing stopping me was me. Here are the things I had to overcome.

The Need to go Fast

This was partially because I had a deadline, but I definitely felt the need to go fast because I have some sort of weird need for speed. Sometimes this isn't the need to go fast as much as the need to not go slow: going slow can sometimes feel really demoralizing. I feel like few things are worse than spending 8 hours debugging an issue that arose from me not understanding that I was just using the wrong build command because I UNDERSTAND NOTHING AND MY EYES ARE BLEEDING.

I had to really embrace going slow. It's not enough to read all the articles and guides. I had to take the time to try them and to really develop an understanding so that I could develop some confidence and move with purpose. The more I invested into testing my understanding and trying out little experiments, the more it cut down on bone-headed debugging sessions. Like writing unit tests, this was well worth my time when learning something new.

I feel like this was tough because my previous positions often called for the opposite. I got into the habit of skimming instead of reading because speed was king, or something was down and actively losing money, or we were running out of runway. While this habit served me well in certain positions, it was not serving me well here.

The Need to go Rabbit Hole-ing

There were times when I asked myself, "why does this part of this framework in this part of the project work this way?" and it would lead to a rabbit hole. I would learn a lot, but at the expense of derailing myself and losing momentum. These kinds of rabbit holes are sometimes disruptive to the learning process, especially if there's a goal or deadline looming. Often times, there's a natural order to the learning of a new skill or framework, and I needed to trust that things would fall in place. It's useful to recognize when something is a rabbit hole and to not follow it all the way through and trust that my questions will be answered in due time. When mentoring others, sometimes I get asked to "skip ahead." I ask them to trust that their question will get answered later in the process and often times get to see the "ah ha!" moment when they are able to answer it themselves. Sometimes I forget to give that to myself.

Rabbit hole-ing is useful for troubleshooting; not so much for learning.

The Need to Judge

Man, this is one I catch myself and a lot of other devs doing a lot. Sometimes I have an idea or model for how the world does work or should work and find things that don't fit into that model to be really, really frustrating. As I'm sitting here writing this I'm wondering why this happens. For me, I think it's a lack of trust. Specifically, a lack of trust that the way a given tool or framework operates is really the best or most effective way to do so. This leads to me being really closed-minded, which sometimes is a useful optimization, but certainly does not serve anyone well when learning or trying to exercise an entrepreneurial mindset. Being closed-minded in these settings is an over-optimization and causes one to throw out ideas or understanding that might have worked.

I had to work really hard to keep reminding myself, "there's probably a good reason this is being done this way." This also kind of ties into the need to go fast. Being open-minded is not a fast thing. Thinking outside your normal box takes a lot of extra time and energy and sometimes feels taxing. I had to trust myself and the tools I was using that they make sense and work and are probably good. I had to have some faith.

The Need to Succeed

Ultimately, success would be having this thing that I developed adopted, loved, enshrined, and awarded a Nobel Peace Prize. That kind of stuff rarely happens, though. Even if I built the best product ever, there's a ton of work that goes into convincing others, overcoming adoption barriers, and actually getting in front of the Nobel Foundation in Sweden (news flash: you can't just walk in). There's also the question of ongoing support and getting feedback and iterative improvements etc, etc.

Finishing this was the goal. I had to keep reminding myself that for the purposes of this project, completion mattered more than anything else. If I never complete anything, then I can't possibly fulfill the rest of the stuff I have listed above as ideal success criteria. Typically, I really struggle with these kinds of mindset changes because I want to skip ahead ("The Need to go Fast"). I really hate lowering my expectations. I sometimes see it as a cheapening of things or experiences. I argue with myself and ask, "why can't I just keep my expectations high and do better?" The short answer is that these things are probably more difficult than I give them credit for and resetting expectations is a form of problem decomposition. I'm not changing my mindset simply so I can feel good. I'm changing my mindset so I can focus on smaller problems as a means of tackling a larger one. It also just so happens that can feel good, too.

So What's my Big Takeaway?

I did it. I showed that I can finish something, even when it involves learning something entirely new and unfamiliar without any external guidance. I have what it takes to really prototype something and to be able to show it off and get feedback in order to achieve the rest of the goal. It wasn't comfortable, and definitely felt questionable, but I suppose if I ever want to prototype products for the real world on my own, I need to embrace that.

Comments

comments powered by Disqus