In my most recent role, we're using Python and Spark to perform a complex ETL process and to produce data that will ultimately be used to produce some model. During this process, we were using PySpark's pyspark.sql.types.DateType to store date information. At some point, we decided that we wanted more precision, so we opted to use pyspark.sql.types.TimestampType instead. When switching, we noticed a considerable slow-down. What once was a processor-intensive task was now failing to occupy all cores of our cluster, causing an obvious slow-down. What gives, Spark? The goal of this post is to explore why this happens in Spark 2.1.1.

Demonstrating the Performance Impact

Before going any further, I suppose that I should give a concrete example of this issue. To make it easy to follow this demonstration, I'm going to use a Docker container provided by Project Jupyter that includes Spark and Jupyter notebook. I'll leave it to the reader to get a container running and a notebook open if they want to follow.

You can see the full notebook here, but for the sake of the article I'm going to be brief. Imagine that you have a dataframe with one million dates and a second one with one million timestamps. Let's call them date_df and timestamp_df, respectively. In order to demonstrate this issue, we need to perform some actions on them. Let's pretend we have the following code:

def date_identity(some_date):

return some_date

def timestamp_identity(some_dt):

return dt

date_identity_udf = func.udf(date_identity, DateType())

timestamp_identity_udf = func.udf(timestamp_identity, TimestampType())

These identity functions don't do anything; they simply return what they're given. Let's try to apply these transformations to their respective data frames. YMMV - the important thing here is not the absolute numbers, but the numbers relative to each other.

transformed_date_df = date_df.withColumn('identity', date_identity_udf(col('some_date')))

timeit.timeit(transformed_date_df.count, number=1)

transformed_timestamp_df = timestamp_df.withColumn('identity', timestamp_identity_udf(col('some_timestamp')))

timeit.timeit(transformed_timestamp_df.count, number=1)

The numbers I got for those calculations, operating on a million items each on a rather large VM was 0.68 and 18.27 seconds, respectively. That means the identity function for the TimestampType took over 26 times longer to run! Where was all of this time going?

Data Serialization and Interlanguage Communication

Spark is not written in Python, so what happens when we write Spark code in Python? In the case that we're doing operations on dataframes and columns, we're simply using Python to build a plan, allowing Spark do all of the work. In this case, little or no actual Python code is run on any of the worker nodes.

What happens when we introduce something like a Python UDF? Well, now we are forcing Spark to run Python code on each of the workers. Spark is not written in Python, so some work has to be done to take data out of the JVM memory model and marshal it into something that Python can interpret and work with. This is in part where some of the pyspark.sql.types module comes in. Let's take a look at the source for one of the dta types:

class TimestampType(AtomicType):

__metaclass__ = DataTypeSingleton

def needConversion(self):

return True

def toInternal(self, dt):

if dt is not None:

seconds = (calendar.timegm(dt.utctimetuple()) if dt.tzinfo

else time.mktime(dt.timetuple()))

return int(seconds) * 1000000 + dt.microsecond

def fromInternal(self, ts):

if ts is not None:

# using int to avoid precision loss in float

return datetime.datetime.fromtimestamp(ts // 1000000).replace(microsecond=ts % 1000000)

(Sorry for the code being hard to read -- I need to fix my theme)

We can see that this class appears to be responsible for marshalling/unmarshalling between Python and Spark data types. The toInternal() method takes timestamps and turns them into Python ints (if you're using Python 3, that is...) and fromInternal() takes an int and returns a datetime. Since our UDF isn't doing any real work, it would lead us to believe that the only task benig carried out is this data conversion. Let's test it to see if we can prove this.

Breaking Apart the Marshalling and Unmarshalling

What we want to do is to time how long it takes to convert date->int, int->date, timestamp->int, and int->timestamp. If any of these pop out at us, then we will be able to narrow down our performance problem.

If you're interested in the code used to test each part of the process, I suggest you take a look at the notebook that was used to run the test. Here are the results I came up with:

- date->int: 0.619 sec, baseline

- int->date: 1.889 sec, ~200% increase

- timestamp->int: 18.260 sec, ~2800% increase

- int->timestamp: 52.889 sec, ~8400% increase

There are a few conclusions we can draw here:

- Dates are always cheaper than timestamps

- Going from a numeric type to a Python

datetime.dateordatetime.datetimeis more expensive than the opposite operation

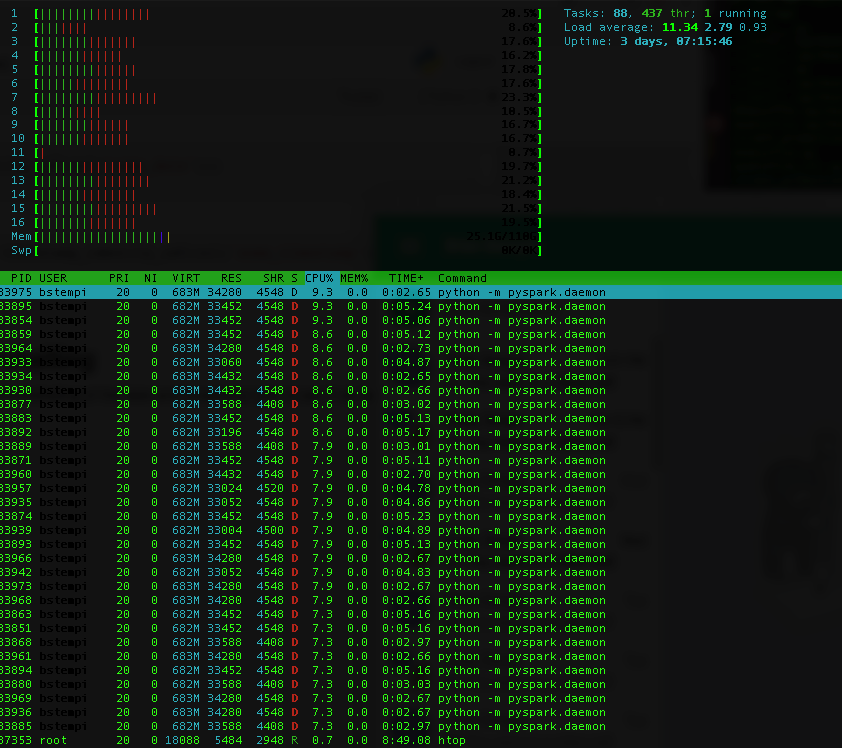

The last thing that I'd like to present is a screenshot of htop. During the date operations, all cores are busy. Here's what it looks like during the timestamp operations:

This is a clear sign of contention.

An Attempt to Circumvent the Contention

At this point, we've identified, on a shallow level, the operations that are causing a slow-down and some contention. I'm not entirely sure why. In order to answer that, I'd really have to dig through the Spark source code. Instead of doing that, I'd like to share an approach that a colleague and I came up with to significantly speed things up.

Instead of doing calculations that return timestamps, we do calculations that ultimately return longs and have Spark cast them to timestamps. Here's an example:

def timestamp_to_long(dt):

"""

This function takes a timestamp and returns it as microseconds from epoc, respecting timezone. If no tzinfo is specified,

UTC is assumed.

:param dt:

:return:

"""

if dt is None:

return None

if not dt.tzinfo:

dt = dt.replace(tzinfo=datetime.timezone.utc)

return int(

((dt - datetime.datetime(1970, 1, 1, tzinfo=datetime.timezone.utc)) / datetime.timedelta(microseconds=1)))

def some_timestamp_function(ts):

# User magic happens here, then we convert to a long

return timestamp_to_long(ts)

ts_udf = udf(some_timestamp_function, LongType())

df = df.withColumn('manipulated_ts', ts_udf(col('some_ts_col')).cast('timestamp'))

How do we know it works? In short, it worked in our case. We had an ETL job that was manipulating about seven billion dates with a UDF which ran sluggisly and had very poor processor utilization. The only change we made was to return longs and cast them...that's it! All of the date math/manipulation/etc happens with the datetime.datetime class withing a pure Python UDF.

So, where's my proof?

I don't really have any...if I were to repeat the tests above where we swap out the identity UDFs for UDFs that return longs, we get similar times. The only explanation that comes to mind is that Spark is able to do additional operations when using our fix that it can't do otherwise, so the increase we see in CPU utilization is not caused by our method of timestamp handling, but rather Spark's ability to do other operations at the same time.

Why this slowdown happens and why my proposed fix works (in my case...YMMV) is a bit of a mystery to me, but I intend to keep trying to find a way to demonstrate it! I'd also be interested to hear if you've had significant slowdowns due to timestamp manipulation or if this fix helps you. Drop me a line, and happy hacking!

Comments

comments powered by Disqus